Karl Marx, his beloved wife Jenny von Westphalen from Prussian aristocratic family, their children Laura and Eleanor and the friend Friedrich Engels

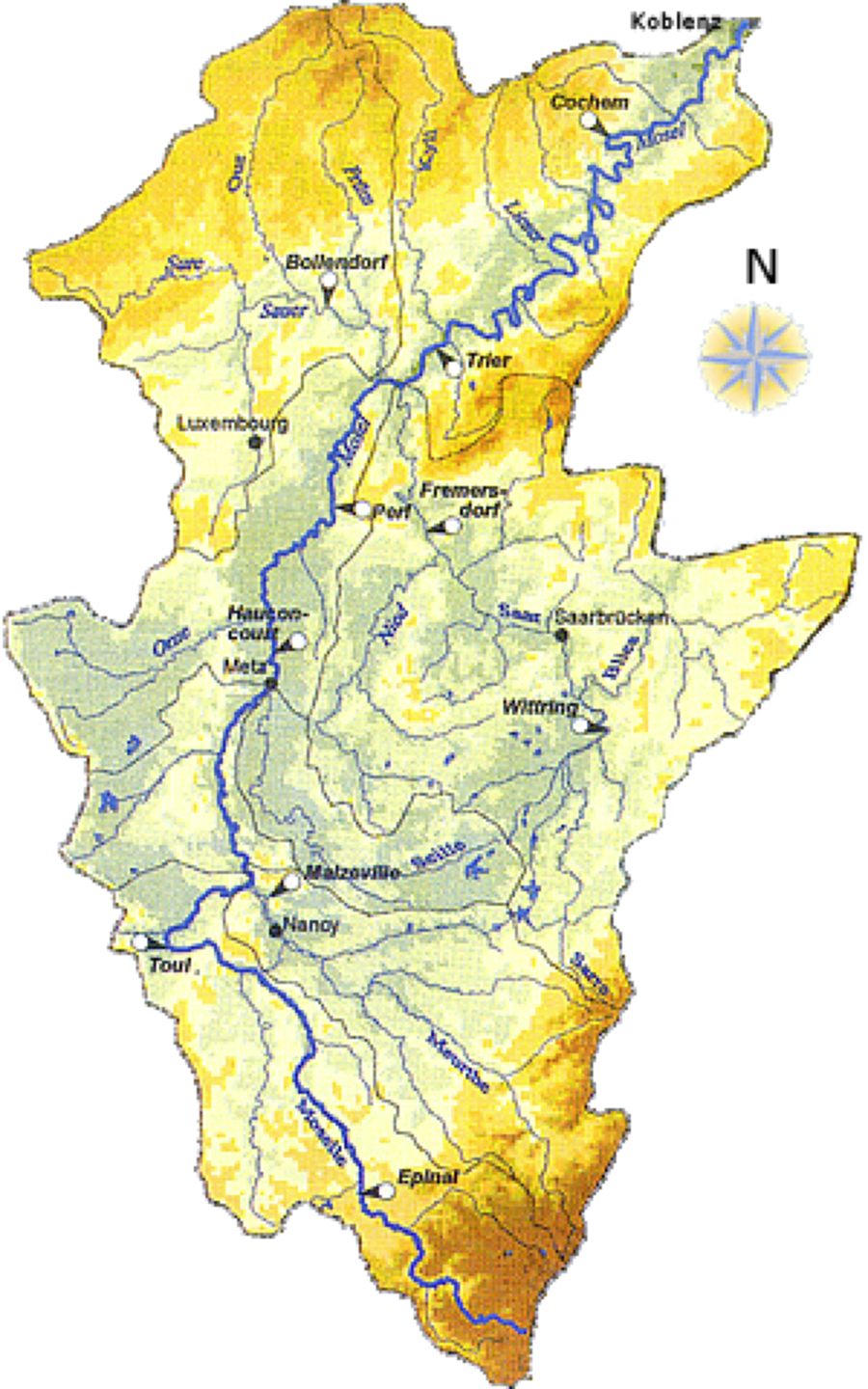

1818, Marx was born in Trier, Trèves, AUGUSTA TREVERORUM with it Roman bridge, baths, gate (Porta Nigra) and Amphitheater that still visible.

Photo by Stefan Kühn, Wikipedia, Creative Commons http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.ca)

«Augusta Treverorum, Porta Nigra, Amphitheater and Circus, Model in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier, built by Joachim Woditsch, Trier» - photos by Stefan Kühn (Wikipedia) Creative Commons (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.it)

The city is a confluence of Latin world, Frankish world and German world on the banks of the Moselle (Mosel)

Trier, Bonn (University), Berlin (University), Jena (University), Cologne, Paris, London a long way for Marx work.

The point of view of Marx from XIX century is very interesting about World reality that influence XXI century and that trancend the vulgata about him work, caused by himself, him vision of classes and dogmatism, the historical environment of him century, and by the opportunistic and simplistic "followers" of XX century that created monstruous political systems without any respect for Persons.

We begin with the follow reading proposal where we can see Portugal:

«Secret Diplomatic History of The Eighteenth Century» Karl Marx (Editor: Eleanor Marx Aveling:

«To understand a limited historical epoch, we must step beyond its limits, and compare it with other historical epochs. To judge Governments and their acts, we must measure them by their own times and the conscience of their contemporaries.»

«Sir George Macartney to the Earl of Sandwich.

"St. Petersburg, 1st (12th) March, 1765."Most Secret.

(...) in case the Spaniards attacked Portugal, we might have 15,000 Russians in our pay to send upon that

service."»

«The oligarchy which, after the "glorious revolution," usurped wealth and power at the cost of the mass of the British people, was, of course, forced to look out for allies, not only abroad, but also at home. The latter they found in what the French would call la haute bourgeoisie, as represented by the Bank of England, the money-lenders, State creditors, East India and other trading corporations, the great manufacturers, etc. Howtenderly they managed the material interests of that class may be learned from the whole of their domestic legislation—Bank Acts, Protectionist enactments, Poor Regulations, etc. As to their foreign policy, they wanted to give it the appearance at least of being altogether regulated by the mercantile interest, an appearance the more easily to be produced, as the exclusive interest of one or the other small fraction of that

class would, of course, be always identified with this or that Ministerial measure. The interested fraction then raised the commerce and navigation cry, which the nation stupidly re-echoed.At that time, then, there devolved on the Cabinet, at least, the onus of inventing mercantile pretexts, however futile, for their measures of foreign policy. In our own epoch, British Ministers have thrown this burden on foreign nations, leaving to the French, the Germans, etc., the irksome task of discovering the secret and hidden mercantile springs of their actions. Lord Palmerston, for instance, takes a step apparently the most damaging to the material interests of Great Britain. Up starts a State philosopher, on the other side of the Atlantic, or of the Channel, or in the heart of Germany, who puts his head to the rack to dig out the mysteries of the mercantile Machiavelism of "perfide Albion," of which Palmerston is supposed the unscrupulous and unflinching executor. We will, en passant, show, by a few modern instances, what desperate shifts those foreigners have been driven to, who feel themselves obliged to interpret Palmerston's acts by what they imagine to be the English commercial policy. In his valuable Histoire Politique et Sociale des Principautés Danubiennes, M. Elias Regnault, startled by the Russian conduct, before and during the years 1848-49 of Mr. Colquhoun, the British Consul at Bucharest, suspects that England has some secret material interest in keeping down the trade of the Principalities. The late Dr. Cunibert, private physician of old Milosh, in his most interesting account of the Russian intrigues in Servia, gives a curious relation of the manner in which Lord Palmerston, through the instrumentality of Colonel Hodges, betrayed Milosh to Russia by feigning to support him against her. Fully believing in the personal integrity of Hodges, and the patriotic zeal of Palmerston, Dr. Cunibert is found to go a step further than M. Elias Regnault. He suspects England of being interested in putting down Turkish commerce generally. General Mieroslawski, in his last work on Poland, is not very far from intimating that mercantile Machiavelism instigated England to sacrifice her own prestige in Asia Minor, by the surrender of Kars. As a last instance may serve the present lucubrations of the Paris papers, hunting after the secret springs of commercial jealousy, which induce Palmerston to oppose the cutting of the Isthmus of Suez canal.»And now we propose readings in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels contributs for Neue Rheinische Zeitung Revue (1850) where we can see the Cape of Good Hope, New Grenada, Panama, about the Isthmus, the link between oceans, the emergency of Pacific (by the United States of America development East to West) that would be replace Atlantic as Mediterrean Sea was replaced, the European Democracy:

«While the Continent has been occupied for the last two years with revolution and counter-revolution, and the inevitable torrent of words which has accompanied these events, industrial England has been busy with quite another commodity: prosperity. Here, the commercial crisis which broke out in due course in the autumn of 1845 was twice interrupted — at the beginning of 1846 by the free trade legislation, and at the beginning of 1848 by the February revolution. Between these two events, a large proportion of the commodities which had been flooding markets abroad gradually found new market outlets, and the

February revolution then removed the competition of continental industry in these markets, while English industry did not lose much more from the disruption of the continental market than it would have lost without

the revolution from a continuation of the crisis. The February revolution, by temporarily bringing continental industry almost to a standstill, helped the English to weather a crisis year quite tolerably; it contributed substantially to clearing accumulated stocks on the overseas markets and made a new industrial boom possible in the spring of 1849. This boom which, moreover, has extended to a large part of continental industry, has reached such a level in the last three months that the manufacturers claim that they have never known such good times — a claim which is always made on the eve of a crisis. The factories are overwhelmed with orders and are operating at an accelerated rate; they are resorting to every possible means to circumvent the Ten Hours Act and to increase working hours; scores of new factories are being built throughout the industrial districts, and old ones are being extended.

Ready money is being loaded onto the market, idle capital is striving to take advantage of this period of general profit; the discount rate is giving rise to speculation and quick investments in manufacturing or in

trade in raw materials; almost all articles are rising absolutely in price; all prices are rising relatively.

In short, England is enjoying the full bloom of 'prosperity'. The only question is how long this intoxication will last. Not very long, at any rate. Many of the larger markets — particularly the East Indies — are already almost saturated. Even now exports are being directed less to the really large markets than to the entrepots of world trade, from where goods can be directed to the more favourable markets. As a result of the colossal productive forces which English industry added in the years 1846, 1847 and particularly 1849 to those which already existed in the period 1843-45, and which it still continues to add to, the remaining markets, particularly in North and South America and Australia, will be likewise saturated; and with the first news of their saturation 'panic' will ensue in speculation and in production simultaneously — perhaps as

early as the end of spring, at the latest in July or August. However, as this crisis will inevitably coincide with great clashes on the Continent, it will bear fruit of a very different type from all preceding crises. Whereas hitherto every crisis has been the signal for further progress, for new victories by the industrial bourgeoisie over the landowners and financial bourgeoisie, this crisis will mark the beginning of the modern English revolution, a revolution in which Cobden will assume the role of Necker.

Now we come to America The most important thing which has happened here, still more important than the February revolution, is the discovery of the Californian gold mines. Even now, after scarcely eighteen months, it can be predicted that this discovery will have much greater consequences than the discovery of America itself. For three hundred and thirty years all trade from Europe to the Pacific Ocean has been conducted with a touching, long-suffering patience around the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn. All proposals to cut through the Isthmus of Panama have come to grief because of the narrow-minded jealousy of the trading nations. The Californian gold mines were only discovered eighteen months ago and the Yankees have already set about building a railway, a great overland road and a canal from the Gulf of Mexico,

steamships are already sailing regularly from New York to Chagres, from Panama to San Francisco, Pacific trade is already concentrating in Panama and the journey around Cape Horn has become obsolete. A coastline which stretches across thirty degrees of latitude, one of the most beautiful and fertile in the world and hitherto more or less unpopulated, is now being visibly transformed into a rich, civilized land thickly populated by men of all races, from the Yankee to the Chinese, from the Negro to the Indian and Malay, from the Creole and Mestizo to the European. Californian gold is pouring in torrents over America and the Asiatic coast of the Pacific and is drawing the reluctant barbarian peoples into world trade, into the civilized world.

For the second time world trade has found a new direction. What Tyre, Carthage and Alexandria were in antiquity, Genoa and Venice in the Middle Ages, what London and Liverpool have been hitherto, the emporia of world trade — this is what New York, San Francisco, San Juan del Norte, Léon, Chagres and Panama will now become. The focal point of international traffic --in the Middle Ages, Italy; in modern times,England — is now the southern half of the North American peninsula: industry and wealth of others, who demanded and still demand a different distribution of property — indeed the total abolition of private property. When Herr Gützlaff came back among civilized people and Europeans after twenty years' absence,he heard talk of socialism and asked what it was. When he was told, he exclaimed in alarm: 'Am I

nowhere to escape this ruinous doctrine? Precisely the same thing has been preached for some time in China by many people from the mob.'

Chinese socialism may, of course, bear the same relation to European socialism as Chinese to Hegelian philosophy. But it is still amusing to note that the oldest and most unshakeable empire on earth has, within

eight years, been brought to the brink of a social revolution by the cotton bales of the English bourgeoisie; in any event, such a revolution cannot help but have the most important consequences for the civilized

world. When our European reactionaries, in the course of their imminent flight through Asia, finally arrive at the Great Wall of China, at the gates which lead to the home of primal reaction and primal conservatism, who knows if they will not find written thereon the legend:

République chinoise

Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité

London, 31 January 1850»

«We now come to the United States of America. The crisis of 1836, which broke out there first and raged most violently, lasted almost without interruption until 1842 and led to a complete transformation of the American credit system. The commerce of the United States recovered on this more solid foundation, if at first very slowly, until from 1842 to 1845 prosperity significantly increased there, too. The rise in

prices and the revolution in Europe only brought benefits for America.

From 1845 to 1847 it profited from the enormous export of grain and from the 1846 rise in cotton prices. In1849 it produced the largest cotton crop to date, and in 1850 it made about $20 million from the loss in the

cotton crop, which coincided with the new boom in the European cotton industry. The revolutions of 1848 caused a large-scale flow of European capital to the United States, which arrived partly with the immigrants

themselves and was partly attributable to European investments in American treasury bonds. This increase in demand for American bonds has forced up their price to such an extent that recently in New York

speculators have been seizing on them quite feverishly. Thus, despite all assertions to the contrary in the reactionary bourgeois press, we still maintain that the only form of state to enjoy the confidence of our European capitalists is the bourgeois republic. There is only one expression of bourgeois confidence in any form of state: its quotation on the stock exchange.

However, the prosperity of the United States increased even more for other reasons. The populated area, the home market of the North American union, extended with surprising rapidity in two directions. The population increase, due both to reproduction within America and to the continuing increase in immigration, led to the settlement of whole states and territories. Wisconsin and Iowa were comparatively densely populated within a few years, and there was a significant increase in immigrants to all states in the upper

Mississippi region. The exploitation of the mines on Lake Superior and the rising grain production in the whole area around the Great Lakes produced a new boom in commerce and shipping on this system of great

inland waterways, which will expand further as a result of an act passed during the last session of Congress, by which trade with Canada and Nova Scotia has been greatly facilitated. While the northwestern states

have thus gained a new importance, Oregon has been colonized within a few years, Texas and New Mexico annexed and California conquered. The discovery of the Californian gold mines has set the cap on American

prosperity. In the second number of this Revue — before any other European journal — we drew attention to the importance of this discovery and its necessary consequences for the whole of world trade.

This importance does not lie in the increased supply of gold from the newly discovered mines, although this ncrease in the means of exchange was bound to have consequences for commerce in general. It lies rather

in the spur given to investment on the world market by the mineral wealth of California, in the activity into which the whole west coast of America and the eastern coast of Asia has been plunged, in the new market outlets created in California and in all the other countries affected by California. Even taken by itself the Californian market is very important; a year ago there were 100,000 people there; now there are at least 300,000 people, who are producing almost nothing but gold, and who are exchanging this gold for their basic living requirements from foreign markets. But the Californian market itself is unimportant compared to the continual expansion of all the markets on the Pacific coast, compared to the striking increase in trade withChile and Peru, western Mexico and the Sandwich Islands, and compared to the traffic which has suddenly arisen between Asia, Australia and California.

Because of California, completely new international routes have become necessary, routes which will inevitably soon surpass all others in importance. The main trading route to the Pacific Ocean — which has

really only now been opened up, and which will become the most important ocean in the world — will, from now on, go across the Isthmus of Panama. The establishment of links across the Isthmus by highways,

railways and canals is now the most urgent requirement of world trade and has already been tackled in places. The railway from Chagres to Panama is already being built. An American company is having the river

basin of San Juan del Norte surveyed with a view to connecting the two oceans, first of all by an overland route and then by a canal. Other routes — across the Isthmus of Darien, the Atrato route in New Granada,

across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec — are being discussed in English and American journals. The ignorance in the whole civilized world about the conditions of the terrain in Central America, which has now suddenly

been exposed, makes it impossible to determine which route is the most advantageous for a great canal; according to the little information available, the Atrato route and the way across Panama seem to offer the

best opportunities. The rapid expansion of the ocean steamer lines has become equally urgent, in order to connect up with the lines of communication across the Isthmus. Steamers are already sailing between

Southampton and Chagres, New York and Chagres, Valparaiso, Lima, Panama, Acapulco and San Francisco; but these few lines, with their small number of steamers, are by no means adequate. The increase in steamer lines between Europe and Chagres becomes daily more urgent, and the growing traffic between Asia, Australia and America requires great new steamship lines from Panama and San Francisco to Canton, Singapore, Sydney, New Zealand and the most important station in the Pacific, the Sandwich Islands. Of all the areas in the Pacific Australia and New Zealand in particular have expanded most, as a result of both the rapid progress of colonization and the influence of California, and they do not want to be divided from the civilized world a moment longer by a four to six-month sea voyage. The total population of the Australian

colonies (excluding New Zealand) rose from 170,676 in 1839 to 333,764 in 1848; that is, it increased in nine years by 95 1/2 per cent. England itself cannot leave these colonies without steamship links; and the

government is negotiating at this moment for a line connecting with the Indian overland post. Whether this linecomes about or not, the sheer necessity of a steamship connection with America, and particularly

California, where 3,500 people from Australia emigrated to last year, will itself produce a solution. It may be said that the world has only become round since the necessity has arisen for this global steam shipping.

This imminent expansion in steam shipping will be increased further by the opening up of the Dutch colonies already mentioned and by the increase in screw steamers, with which — as is becoming increasingly

clear — emigrants can be transported more rapidly, relatively cheaper and more profitably than with sailing ships. Apart from the screw steamers which already sail from Glasgow and Liverpool to New York, new

ones are to be employed on this line and a shipping line is to be established between Rotterdam and New York. How universal is the present tendency for capital to flow into oceanic steam shipping is proved by

the continuous increase in the number of steamers competing between Liverpool and New York, the establishment of entirely new lines from England to the Cape and from New York to Le Havre, and a whole series of similar schemes which are being hawked around New York.

With the investment of capital in oceanic steam shipping and the building of canals across the American isthmus the ground has already been laid for excess speculation in this area. The centre of this speculation is necessarily New York, which receives the great mass of Californian gold. It has already taken control of the main trade with California and in general performs the same function for the whole of America as London does for Europe. New York is already the centre of all transatlantic steam shipping. All the Pacific steam ships belong to New York companies, and almost all new projects in this branch of industry start in New York. Speculation in foreign steamship lines has already begun in these, and the Nicaragua Company, which was launched in New York, similarly represents the beginning of speculation in the isthmus canals. Overspeculation will soon develop, and even though English capital is flowing en masse into all such undertakings, even though the London Stock Exchange will be inundated with all sorts of similar schemes, New York will still remain the centre of the whole bubble, this time as in 1836, and will be the first to experience its collapse. Innumerable schemes will be ruined, but as with the English railway system in 1845, at least the outline of a universal shipping system will this time emerge from this over-speculation. No

matter how many companies go bankrupt, the steamships — which are doubling the Atlantic traffic, opening up the Pacific, connecting up Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and China with America and are

reducing the journey around the world to four months — the steamships will remain.

The prosperity in England and America soon made itself felt on the European continent. As early as summer 1849 the factories in Germany, particularly in the Rhine province, were quite busy again, and since the

end of 1849 there has been a general recovery of business. This renewed prosperity, which our German bourgeois naively attribute to the restoration of stability and order, is based in reality only upon the

renewed prosperity in England and upon the increased demand for industrial products on the American and tropical markets. In 1850 industry and trade have recovered even further. Just as in England, there has been a temporary surplus of capital and an extraordinary easing of the money market, and the reports of the Frankfurt and Leipzig autumn fairs have reportedly been extremely satisfactory for the bourgeoisie taking part. The troubles in Schleswig-Holstein and Electoral Hesse, the quarrels within the Prussian Union and the threatening notes exchanged between Austria and Prussia have not been able to hold back the

development of all these symptoms of prosperity for a moment, as even the Economist noted, with mocking cockney smugness...

(...)

We now come to the abstract country, the European nation, the nation of the exiles. We shall not mention the individual groups of exiles, the Germans, French, Hungarians, etc; their haute politique is limited to pure chronique scandaleuse.

But Europe and the people as a whole have recently been given a provisional government in the form of the European Central Committee, consisting of Joseph Mazzini, Ledru-Rollin, Albert Danu (the Pole) and — Arnold Ruge, who modestly justifies his presence by writing 'member of the Frankfurt National Assembly' after his name. Although it is impossible to say which democratic council has called these four evangelists to office, their manifesto undeniably contains the creed of the broad mass of the exiles and summarizes in fitting form the intellectual achievements which this mass owes to the recent revolution.

The manifesto begins with a pompous enumeration of the strengths of democracy.

"What does democracy lack for the achievement of its victory?... Organization... We have sects but no church, incomplete and contradictory philosophies but no religion, no collective belief which can assemble the believers under a single sign and harmonize their work... The day on which we find ourselves all united, marching together under the eyes of the best among us... will be the eve of the struggle.

On this day we shall have counted our numbers, we shall know who we are, we shall be conscious of our power.

Why has the revolution not yet succeeded? Because the organization of revolutionary power has been weak.This is the first decree of the exiles' provisional government.

This state of affairs is to be remedied by the organization of an army of believers, and the founding of a religion.

But to achieve this two great obstacles must be surmounted, two great errors overcome: the exaggeration of the rights of individuality, the narrow-minded exclusiveness of theory... We must not say T: we must learn to say 'we'...those who follow their individual susceptibilities refuse to make the small sacrifices demanded by

organization and discipline and deny the total body of beliefs which they preach, as a result of the habits of the past... Exclusiveness in theory is the negation of our basic dogma He who says, 'I have discovered a political truth,' and who makes the acceptance of his system into a condition of acceptance into the fraternal association, disavows the people — the only progressive interpreter of the world law — merely in order to assert his own ego. He who maintains that be is able today to discover a definitive solution to the problems which activate the m by means of the isolated labour of his intellect, however powerful it may be, condemns himself to the error of incompleteness by abandoning one of the eternal sources of truth: the collective intuition of the people in action. The definitive solution is the of our victory... Far the most part our systems can be nothing but a dissection of corpses, a discovery of evil and an analysis of death, incapable of

perceiving or comprehending life. Life is the people in movement, the instinct of the masses raised to an extraordinary power by common contact, by the prophetic feeling of great things to be achieved, by

spontaneous, sudden, electric association in the street. It is action, exciting to their highest pitch all the latent powers of hope, devotion, love and enthusiasm which are now dormant, revealing man in the unity

of his nature, in the full vigour of his potency. The handshake of a worker at one of those historic moments which begin an epoch will teach us more about the organization of the future than can be taught today by

the cold and heartless labour of reason or by knowledge of the illustrious dead of the last two millennia of the old society."

So, in the end, all this highfalutin nonsense amounts to the highly vulgar and philistine view that the revolution failed because of the jealous ambition of the individual leaders, and because of the conflicting opinions of the various popular teachers.

The struggles of the different classes and fractions of classes with one another, which in their development through specific phases is precisely what constitutes the revolution, are, for our evangelists, only the unhappy consequence of divergent systems. However, the divergent systems are in reality the result of the existence of class struggles. It becomes clear even from this that the authors of the manifesto deny the existence of the class struggle. Under the pretext of fighting the doctrinaire they dispense with all specific realities of the situation, all specific partisan views. They forbid the individual classes to formulate their interests and demands in the face of other classes. They expect the classes to forget their conflicting interests and to reconcile themselves under the banner of something hollow and brazenly vague, which, in the guise of reconciling the interests of all parties, only conceals the domination by one party and its interests —

the party of the bourgeoisie. After what these gentlemen must have experienced in France, Germany and Italy during the last two years it cannot even be said that the hypocrisy by means of which they wrap

bourgeois interests in a Lamartinian rhetoric of brotherhood is unconscious. How much the gentlemen know about 'systems' is shown, moreover, by the fact that they imagine each of these systems to be merely a fragment of the wisdom compiled in the manifesto, and to be based solely on one of the rhetorical phrases assembled here: freedom, equality, etc. Their notions of social organization are highly striking: a riot in the street, a brawl, a shake of the hand, and that is that!

For them the whole revolution consists merely in the overthrow of the existing governments; once this aim hasbeen achieved, 'victory' will have been won. The movement, the development, the struggle then comes to

an end, and under the aegis of the then ruling European Central Committee the golden age of the European Republic and the permanent rule of the nightcap can begin. Just as they hate development and struggle,

these gentlemen hate thought, callous thought — as if any thinker, including Hegel and Ricardo, would ever have achieved that degree of callousness with which this mealy-mouthed swill is poured over the heads

of the public. The people are not to worry about the morrow, they must empty their heads of ideas. When the great day of decision comes, they will be electrified by mere physical contact and the riddle of the

future will be solved for the people by a miracle. This summons to empty-headedness is a direct attempt to swindle precisely those classes who are most oppressed. One member of the European Central Committee

asks,

In saying this, do we mean that we are to march on without a banner; do we mean that we wish to inscribe a negation on our banner? Such a suspicion cannot be directed at us. As men of the people, who have been part of the struggle for many years, we do not for one moment consider leading them into an empty future.

On the contrary, to prove the fullness of their future these gentlemen present a record — worthy of Leporello himself — of eternal truths and achievements from the whole course of history. This record is put forward as the common ground of 'democracy' in our day and age and is summed up in the following edifying

paternoster:

"We believe in the progressive development of human ability and strength towards the moral law which has been imposed upon us. We believe in association as the only means to achieve this end. We believe that the interpretation of this moral law and the law of progress can be entrusted to the charge of neither a caste nor an individual, but to the people, enlightened by national education, led by those from its midst whom virtue and the people's genius show to be the best. We believe in the sacredness of both individuality and society,

which should never exclude nor conflict with each other, but should harmonize for the betterment of all by all. We believe in freedom, without which all human responsibility disappears; in equality, without which freedom is only an illusion; in brotherhood, without which freedom and equality would be means without an end; in association, without which brotherhood would be an unrealizable programme; in family. community, state and fatherland as equally progressive spheres which man must successively grow into, in the knowledge and application of freedom, equality, brotherhood and association. We believe in the sanctity of work and in property which arises from work as its symbol and fruit; we believe in the duty of society to provide the means for material work through credit and the means for mental work through education... to sum up, we believe in a social condition which has God and His law as its apex, and the people as its base..."

So: progress — association — moral law — freedom — equality — brotherhood — association — family, community, state — sanctity of property — credit — education — God and the people — Dio e popolo.

These phrases figure in all the manifestoes of the 1848 revolutions, from the French to the Wallachian, and it is precisely for that reason that they figure here as the common basis of the new revolution. In none of these revolutions was the sanctity of property, here sanctified as the product of work, forgotten. Eighty years before their time Adam Smith knew much better than our revolutionary pioneers the precise extent to which bourgeois property is 'the fruit and symbol of work'. As for the socialist concession that society shall grant everyone the material means for work through credit, every manufacturer is accustomed to give his worker credit for as much material as he can process in a week. The credit system is as widely extended nowadays as is compatible with the inviolability of property, and credit itself is after all only a form of bourgeois property.

Summarized, this gospel teaches a social order in which God forms the apex and the people — or, as is said later, humanity — the base. That is, they believe in society as it exists, in which, as is well known, God is at the apex and the mob at the base. Although Mazzini's creed, God and the people, Dio e popolo, may have a meaning in Italy, where the Pope is equated with God and the princes with the people, it is a bit much to offer this plagiarism of Johannes Ronge, the most insipid swill of the German pseudo-Enlightenment, as the key which will solve the riddle of the century. Furthermore, how easily the members of this school accustom themselves to the small sacrifices which organization and discipline demand, how willingly they give up the

narrow exclusiveness of theory is demonstrated by our friend, Arnold Winkelried Ruge, who, to Leo's great joy, has this time been able to recognize the difference between divinity and humanity.

The manifesto ends with the words:

"What is needed is a constitution for European democracy, and the foundation of a people's budget or exchequer. What is needed is the organization of an army of initiators."

In order to be one of the first initiators of the people's budget Ruge has turned to 'de demokratische Jantjes van Amsterdam' — the democratic citizens of Amsterdam — to explain to them their

special vocation and duty to provide money. Holland is in distress!

London, 1 November 1850»

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário

Muito obrigado pelo seu comentário! Tibi gratiās maximās agō enim commentarium! Thank you very much for your comment!